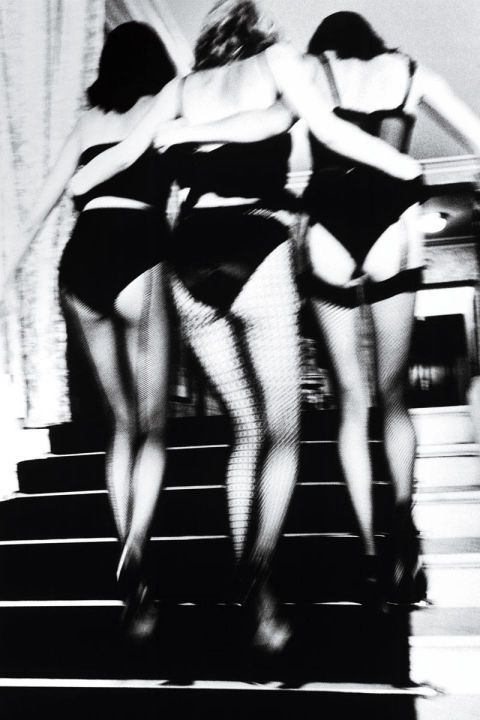

© Ellen von Unwerth/Art + CommerceAdvertisement - Continue Reading BelowA group of young women—ranging in age from their early twenties to early thirties—have gathered in my apartment ostensibly to talk about fundraising for an online magazine, but along the way we segue into a discussion of Girls, Fifty Shades of Grey, Internet porn, the mandatory denuding of pubic hair, and all the rest of the phenomena that seem to characterize the present erotic moment. These young women routinely refer to men as dudes and appear to be at ease with casual sex—speaking dispassionately about their experiences, reducing them to amusing anecdotes—in a way that was once seen as more true of men. I find myself wondering whether this has been all to the good, whether some essential frisson has been lost along with the traditional self-consciousness about sex. I think of the film director Luis Buñuel's famous statement, "Sex without sin is like an egg without salt," which I've always taken to mean that sexual satisfaction requires an edge—that without some sort of impediment to bump up against, we risk vertigo-inducing psychological free-fall.

© Ellen von Unwerth/Art + CommerceAdvertisement - Continue Reading BelowA group of young women—ranging in age from their early twenties to early thirties—have gathered in my apartment ostensibly to talk about fundraising for an online magazine, but along the way we segue into a discussion of Girls, Fifty Shades of Grey, Internet porn, the mandatory denuding of pubic hair, and all the rest of the phenomena that seem to characterize the present erotic moment. These young women routinely refer to men as dudes and appear to be at ease with casual sex—speaking dispassionately about their experiences, reducing them to amusing anecdotes—in a way that was once seen as more true of men. I find myself wondering whether this has been all to the good, whether some essential frisson has been lost along with the traditional self-consciousness about sex. I think of the film director Luis Buñuel's famous statement, "Sex without sin is like an egg without salt," which I've always taken to mean that sexual satisfaction requires an edge—that without some sort of impediment to bump up against, we risk vertigo-inducing psychological free-fall.More From ELLEWhat strikes me as truly strange, however, is this: I'm older than these women and should by all rights be envious of their paradise of sexual opportunities, but I find myself feeling sorry for them instead—just as I winced when I watched Girls, finding it as sad as it was funny. I've read various defenses of the show's deflated rendering of sexual engagement, and I'm still not convinced that the pivotal scene—in which Adam (played by Adam Driver) masturbates over the awkwardly naked body of Hannah (played by Lena Dunham) to the tune of a vocalized fantasy about her being an 11-year-old druggie—is impressive for its candor so much as dreary in its implications.

For one thing, what is so new, much less revelatory, about autoeroticism and a young man's "wanton absorption" in it? Why on earth would it engage the viewer, as Elaine Blair suggests in The New York Review of Books, more than Hannah's flustered attempts to connect at all costs, even if that means going along with said fantasy? "We can feel the erotic charge of the scene," writes Blair, "in spite of its limitations, qua sex, for Hannah. We can contemplate Hannah's lack of sexual confidence without condemning Adam. We can appreciate, rather than lament, Hannah's attraction to Adam despite the fact that he is wont to do things like dismiss her from his apartment with a brusque nod while she is still chatting and gathering her clothes and purse."

Related: A Different Way of Thinking About Lena Dunham's Nudity on 'Girls'

Can we? Perhaps, if we don't have our own identification with Hannah—and our own hopes on her behalf for something approaching sexual fulfillment (not to mention a little love). Unless we're all irretrievably jaded voyeurs by now, on the lookout for the next debased thrill, it seems to me that the erotic context is still potent with promise for many of us, remaining one of the last outposts of the unironic in a culture bent on demystifying every last experience. Or, at least, it ought to be, if we weren't so set these days on undercutting its power by holding it up to the light and examining it. What, one might ask, happened to the blissed-out dream of sex that came with the Sexual Revolution, the promise of intense intimacy and naked abandon—sex as "the long slide/ To happiness, endlessly" that the British poet Philip Larkin envisioned in his poem "High Windows"? Why does it seem to have been cast aside in favor of a more banal discourse, one bleached of excitement and mystery?

Let me make clear where I'm coming from. I'm not trying to speak for the joys of good, old-fashioned sex as against current subversions/perversions thereof. I'm not even sure I believe in such an entity as good, old-fashioned sex. Sexual arousal, to the extent that it takes place in the brain as much as in the body, is one of the most subjective of all pleasures, encoded in highly individualized scripts that contain our psychic histories in the form of charged images and fantasies. The details of these scripts—or "microdots," as the psychiatrist Robert Stoller calls them in his book Sexual Excitement—are designed to reproduce and, ideally, repair past traumas and humiliations that we carry with us from childhood. But as Stoller points out on the very first page of his book, the phrase "sexual excitement" is itself woefully inexact: "Sexual has so many uses," he observed, "that we scarcely comprehend even the outer limits of what someone else indicates with the word; does he or she refer to male and female, or masculinity and femininity, or eroticism, or intercourse, or sensual, nonerotic pleasure, or life-force?"

I should point out as well that my own tastes have historically run to the edgier end of the sexual spectrum—and, indeed, in some circles I am seen as a promoter of unsavory sexual preferences. I am referring to a lengthy essay I wrote for The New Yorker in 1996 called "Unlikely Obsession." This piece, which has continued to haunt me from the moment it appeared, was a graphic account of my longtime fascination with erotic spanking and my cautious flirtation with more serious S&M; it also attempted to trace the psychological origins of my interest and to envision a future less tied to this kind of scenario. "The fact is," I wrote early in the piece, "that I cannot remember a time when I didn't think about being spanked as a sexually gratifying act, didn't fantasize about being reduced to a craven object of desire by a firm male hand…."

Advertisement - Continue Reading Below

No comments:

Post a Comment